Devlog

Jun 2, 2025Lets talk about difficulty design in puzzle games

One notoriously difficult task when it comes to designing puzzle games is how to balance difficulty. The reason for this, as is so often the case with design tasks, is that it isn’t a matter of finding the correct solution, but to achieve a fine balance of factors. Make the difficulty too hard and the ramp too steap and many players will drop of before they even get to the interesting parts of the game, make it too shallow and it can feel tedious and boring (or you’ll have to find other motivating factors, like making really smooth and satisfying level solved animations).

In this devlog we will try to explore how our approach changed between our last two puzzle games Chronescher and TRAILS and what we have hopefully learned and improved upon.

Learnings from Chronescher

With our last puzzle game we set out to create a game that used fun mind bending mechanics such as escher style perspective shifts, portals and level state resetting snapshots, and really push them to their limits in order to see what complex interactions they could create.

While we managed to do that, we might have gotten carried away a bit when it comes to the complexity in some of the later levels (after hundreds of hours designing, testing and tweaking levels you kind of lose touch with the experience of a player who has just started to play the game).

Only about 20% of steam players managed to reach Biom 4.

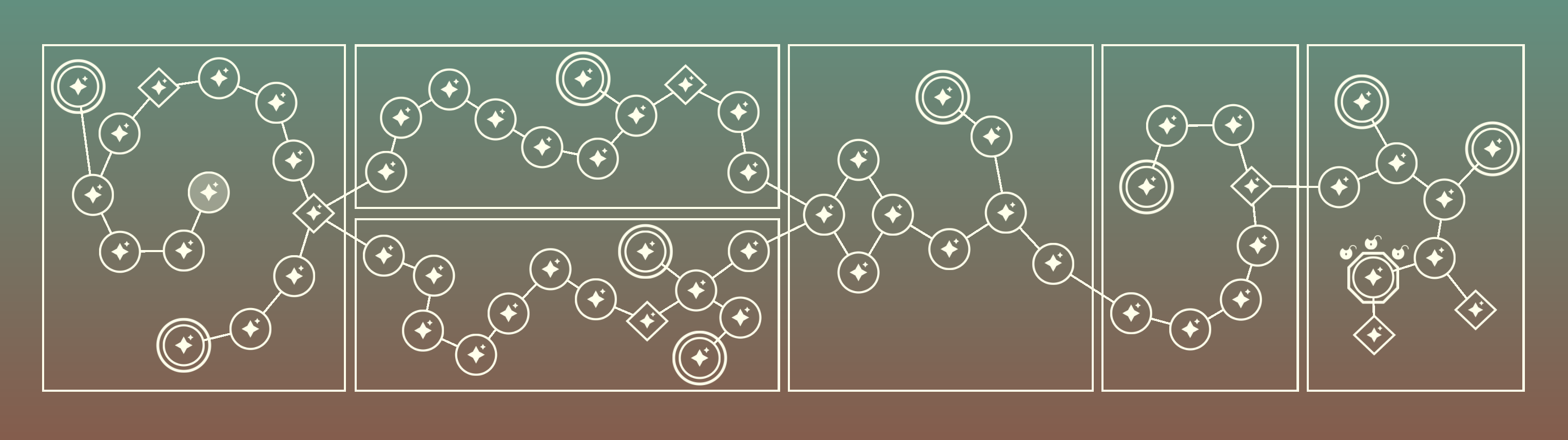

We were aware that some of the levels were getting quite difficult (some of them taking us multiple attempts and several hours on our first solves) and tried to accommodate this by placing them on optional branches. While this worked somewhat well, an internal evaluation of the difficulty curve of chronscher a good year after its launch still revealed multiple problems:

- there were a few instances where levels represented too big of a jump in difficulty, leading some players to give up in frustration

- some mechanics weren’t taught as well as we would have liked, leading to players aimlessly attempting levels in a trial and error fashion, because they didnt have the knowledge required to figure out the solution

- optional levels were not sufficiantly marked as optional (and potentially much more difficult), leading people to get stuck in them early on

- intended to provide a first exploratory stage to many levels, some players disliked that there was no consistent and clear indication what effect a button would have without actually reaching and activating it

On to Trails

With TRAILS our aim was to learn from the things that didn’t work as well in Chronescher.

This meant that we were much more conscious of the ramp in difficulty and tried to achieve as smooth of a learning curve as possible. We also added some additional simple levels after the introductory levels of each mechanic that would reinforce what players had learned and give them an additional opportunity to observe how things worked and interacted with other systems.

Players will only return to the map if they reach a dead end or navigate there themselves.

We also decided not to throw players back onto the main map every time they unlocked a sidepath. This way players were more likely to progress along the main path for their first few sesssions and would likely only attempt the optional challenges when they had settled into the game and were familiar with its core functionality.

We also made the hardest levels even more inaccessible, by gating them behind a late game mechanic that players would only encounter in the second half of the game and only if they played optional levels to begin with. While this setup is a bit convoluted, it grants us much finer control over what difficulty players will encounter at what point of their playthrough, while also adding some excitement and sense of progression to the late game.

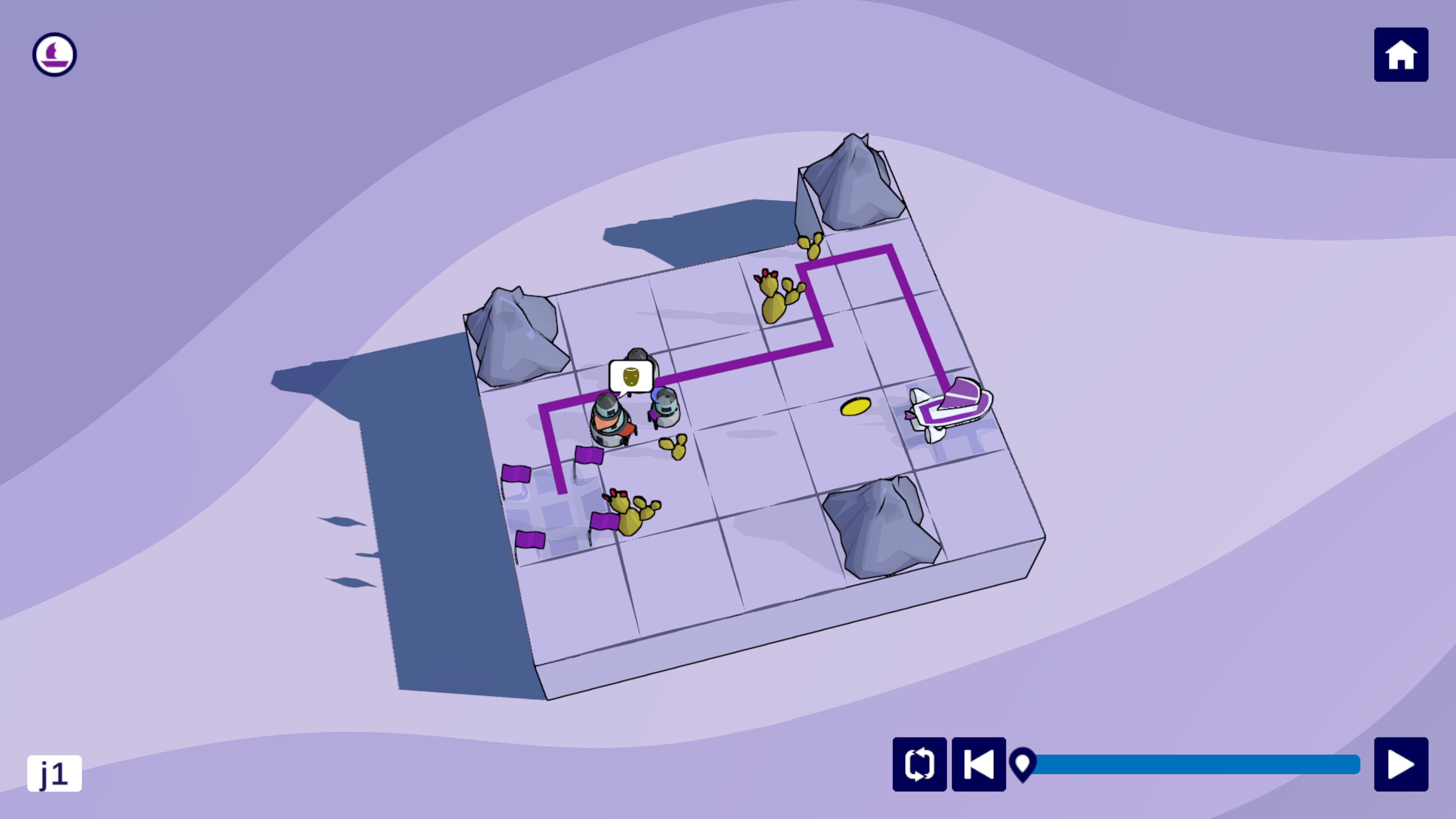

Players need to solve levels with the coin mechanic in order to collect up to 7 coins, that will in turn unlock the three levels of the midnight biome.Coin Levels are all optional levels and hidden until the Coin tutorial (level j1) has been beaten.

Where to next?

In spite of rigorous testing it will take some time after the release of TRAILS for us to be able to properly gauge how well our approach to difficulty in TRAILS ended up turning out. And there will almost certainly be more to improve when we set out next time to make a puzzle game that is both easily picked up and approachable and that also takes its mechanics to the limit, providing challenges for even the most seasoned puzzlers out there.

Article

Oct 25, 2022The following Article is based on interviews Daniel Ziegener conducted with our studio as well as Randwerk and was originally published on Superlevel.de in German. We publish a translated version of the original article with the kind permission of the author.

Games are political and so are the companies that make them

The developers of Abriss and Chronescher don’t want to be start-ups. Instead, they are testing alternatives - as far as that is legally possible.

The fact that the games industry has a problem has been known far longer than the recent strikes at Activision Blizzard King last year. Accusations of massive overtime - known as crunch in industry parlance - and toxic, often misogynistic work environments have been lining up for a long time.

The realization that small, supposedly fine indie studios don’t automatically do better is just beginning to seep into the consciousness of the gaming community. The YouTube channel People Make Games collected examples of power abuse at Fullbright and Funomena in the spring, and sources describe the work atmosphere at Ori developer Moon Studios as “oppressive.” Small studios seem to reproduce the abuse-prone power imbalance of the AAA industry.

Some developers are therefore asking a rather radical question: can companies and employers be good for people at all? The Berlin-based teams of Randwerk and Purple Sloth at least try to find an answer to this question - and therefore found cooperatives instead of companies.

“Togetherness, co-determination, self-realization and so on”.

“There is a political dimension, of course” states Johannes Knop about the founding of Randwerk. Together with his two fellow students Friedrich Beyer and Till Freitag, he developed Abriss. But instead of a GmbH, UG or GbR, [All of those are German legal entities] they founded an eG - a registered cooperative. All members have equal shares in the company.

Apart from a formal legal person in charge, there are no bosses, not a single owner of the company, no one who can decide over everyone else. “We’ve seen how the start-up world tends to work. Even in indie studios, with flat hierarchies, there tends to be conflict, since ownership is limited to few,” he says. “That doesn’t fit together very well.”

Since teamwork functions as a democratic process, everyone really should be equal owners, too. “Maybe what the start-up concept promises ideologically is somewhat more realizable this way,” Knop thinks: “Compared to employment in a large corporation, somehow relaxed working, social interaction, co-determination, self-realization and so on.”

Role models can be found mainly internationally

The cooperative is anchored in German law and has a long history. That game studios choose this legal form is unusual so far. Randwerk and Purple Sloth are among the first. Knop, Beyer and Freitag had been working on concepts of democratic workplace design for some time. But they found concrete examples mainly abroad.

For example, Scott Benson and Bethany Hockenberry, who worked on Night in the Woods, founded The Glory Society, a cooperative that says it doesn’t need bosses; the roguelike Dead Cells was developed by the French cooperative Motion Twin. The game proves that even the business-skeptic business form is capable of producing a hit.

Motion Twin is also an example that shows the limits of a purely cooperative approach. After commercial success, part of the team split off to develop new content for Dead Cells - and, under the self-deprecating name Evil Empire, now does so as a company with a classic decision-making hierarchy. Motion Twin are one of the best-known examples of a company that doesn’t want to be a company.

Cooperatives as an expression of emancipation.

That name, the Evil Empire, the studio has given itself as a warning against what you don’t want to be. “We’re all aware of how easy it can be to exploit ourselves,” Purple Sloth’s Radow also says. “Taking care of yourself, rather than just wanting to create a particularly beautiful product, is a challenge and one we all value accordingly.”

The members of Purple Sloth see themselves as “left-wing, queer-feminist and emancipatory” and position themselves not only with their games, but already with their company. Before founding their cooperative last year, they practiced game development “as an intense hobby, so to speak,” Radow says.

With the puzzle game Chronescher, their first commercial project appeared at the end of August after numerous game jam prototypes. In their search for a suitable legal form, they also ended up with the cooperative. This was “not without alternative, but comes closest to the collective idea”, which has been important to the team since they joined forces. “Already anchored in law, the goal of a cooperative is the economic and social promotion of the members, not the profit of the company, as it would be with GmbH, UG and AG,” Radow explains.

You have to cultivate a different culture

Especially with indiegames that - like Demolition and Chronescher - are born out of friendships and hobby projects, the crunch hides behind the passion that brought them to game development. This romanticized self-exploitation is sometimes learned early on by young developers, for example at game jams.

“Essential to confronting this problem is the office culture we have,” Radow says. “There are no bosses who can demand more output or more hours from the top down.” Instead, Purple Sloth members would watch out for each other “that we don’t sit in the office significantly longer than agreed - and if that does happen, then work correspondingly less in the coming weeks.”

They would also have kept that in mind when drafting their bylaws and employment contracts. These, they said, were created from the perspective of an employee, not an employer. “That means, for example, that we work with a 3-4 day week from the start to avoid Crunch getting a foothold in the first place.”

As founders, these young developers have it in their own hands to set the conditions for their work. Instead of changing an established employer from the inside, they tear it all down - and rebuild it according to their own vision.

There’s a movement behind Demolition and Purple Sloth

The developers of Abriss and Chronescher are not alone in Germany. An entire movement is forming to find even better solutions. With the Purpose Foundation and Stiftung Verantwortungseigentum, two groups have been lobbying for several years to establish a new type of company.

This seems necessary, since things look dire for democratic structures within German game studios. Apart from the exceptions Bigpoint and Massive Miniteam, there is no development studio in Germany that has established a workers council. This is a simple, legally anchored means of balancing the power imbalances between bosses and employees.

In 2020, the Berlin SPD considered linking start-up funding to the establishment of a workers council. A similar approach would also be conceivable for games funding. According to the Ministry of Transport, which was initially still responsible, almost all projects from the pilot phase of games funding were submitted by small and medium-sized enterprises anyway - and 87 percent by micro-enterprises with fewer than ten employees. Exactly the company size in which the coop model works ideally.

“It’s just a bit like getting married, too.”

Both Purple Sloth and Randwerk have entered into more of a marriage of convenience with the registered cooperative. In the end, every company in Germany needs a legal form, and the cooperative is just about the closest thing to the idealistic ideas of both teams.

For this relationship to work, all members of the cooperative have to look out for each other. “The fact that everyone has a say has its problems, of course; it’s just a bit like getting married,” says Johannes Knop. “You really have to know who you’re doing it with.”

This is because “as game creators, our responsibility and our claim is to deal with the political dimension of media” as Radow of Purple Sloth puts it. Both teams leave no doubt that their games are political. But they go one step further: For them, the company itself is political.

Instead of founding a start-up out of university with a business plan and filling out grant applications, Purple Sloth and Randwerk have thought about how they want to work. In this way, these young cooperatives show that alternatives to the problem-ridden games industry of the past are possible.

Interview

Feb 21, 2020Gaming, Politics and Empowerment

This interview was conducted by Verena Grün and originally published by the awesome Lotta magazine, an antifascist publication based in west Germany. Since it is only available in German on their site we have translated the interview and publish it here ourselves.

Is gaming apolitical?

fuchsi*: No. Simple answer: No published media is ever apolitical. If it claims to be, chances are it just supports the status quo, which oviously is quite political.

ente: In particular questions like which stories are being told and from what perspective, are obviously political. All games tell some form of story. Even non narrative-driven games have a setting, a world they take place in and figures that act.

radow: Even gameplay mechanics have a political dimension: Which actions does the game reward and which does it punish?

ente: And what level of experience and which abilities are required to play the game in the first place? Recently there has been a lot of debate around difficulty, gatekeeping and accesibility.

radow: I think it’s worth examining why so many seem to be averse to

the notion of games being political in the first place. Over the last

years we’ve experienced a push for the depolitisation of games. Parts of

the community use slogans like “get politics out of games” to basically

frame anything they perceive as even rudimentary progressive (such as

more diverse characters) as “PC” or “SJW” and claim that it is

“destroying gaming”.

Sadly, the reaction of many AAA studios and publishers isn’t

particularly encouraging either. Even when they do include more diverse

casts and narratives (be this in order to reach a broader audience, or

because of increasingly diverse developers including their own

experiences) they often deflect and claim “our games are not political”.

What unites you as a collective?

ente: Purple Sloth was formed in early 2018, when some of us were

working together as part of a game jam. From there on out things

developed further and we figured out what kind of games we wanted to

make. As indie game developers it is particularly important to us to

foster a welcoming atmosphere of solidarity in which we can develop

games with political subtext. We want to empower ourselves as well as

others with our games. Since many of us fall under the queer umbrella it

is particularly important to us to reflect our experiences as queer

people in our games.

If you want to know more about us and our concept you can find our full

mission statement at: https://purplesloth.studio/mission/

fuchsi*: Games have always been important to many of us. Experiencing compelling stories, finding accomplishment in achievable challenges, fully immersing oneself into a fictional world to forget the problems of the real world for a moment or simply finding inspiration in a crafted experience. Then there is the social aspect: interacting with others in online games or huddling around a screen in order to solve a puzzle game can be powerful connecting experiences. Since we were often missing certain political perspectives or even outright clashed with the standpoint perpetuated by some games we soon found a shared vision for what kind of games we wanted to play – and by extension make.

Is there emancipatory potential in games? Where and why?

fuchsi*: Absolutely! Games have the ability to portray a wide range

of experiences and life circumstances. There are a couple of games that

deal with depression and anxiety or queer experiences and communities.

These tend to be small games more often than not, but they give the devs

behind them a medium to express themselves and share their experiences.

Examples include “Celeste”, “Sea of Solitude”, “Tomorrow don’t come” or

“A Normal Lost Phone”.

As interactive media games are uniquely qualified to convey experiences

and perspectives that may otherwise be foreign to the consumer. They do

not only appeal to the depicted communities, but can also serve to

heighten visibility for them and their struggles. While games may not be

able to fully covey what living with depression is like for example,

their interactive nature allows a player to experience more of it than

is possible in other media.

I think the potential of games in this regard is far from being fully

realized, but developers are starting to explore it.

ente: Another aspect are communities that form around games. These usually exist primarily online and thus are able to bridge distances that would otherwise make them unlikely. Such communities can be safe havens that give support to people who cannot find it in their immediate surroundings.

radow: And even the creation of games in itself can bring people together. In particular I’m thinking of game jams like the ’nonbinary game jam’ or the communities formed around particular game engines. With “Game Workers Unite!” there is finally a global movement for unionization of game devs. That is absolutely necessary, but still met with harsh resistance on the side of many studios and publishers.

With Christchurch, El Paso and Halle there have been several right-wing terror attacks performed by gamers. What was you reaction when you found out about these attacks? Is there any discussion about the connection between right wing terror and gaming in the community?

radow: I’m sad to say that I was not particularly surprised. Over the last years, specifically after GamerGate, right wing activists have identified gaming communities as a plentiful recruitment area. By now they have created outright recruitment pipelines that start in relatively harmless gaming discords and subreddits, moves via GG subreddits and ends on platforms such as 8chan or gab. With good reason 8chan is the platform where the terrorists have shared their manifestos and live streams.

fuchsi*: The source for these problems are neither inherent nor exclusive to games though. They thrive on the acceptance of and alignment towards toxic parts of the communities without any awareness for these problems.

radow: An ever present example is the acceptance of racism under the guise of jokes, memes or alleged historic accuracy (that tends to be all but historically accurate). Racists rants and outbursts from large content creators such as Pewdiepie are belittled as “heated gamer moments”. And large publishers such as THQ Nordic hold AMAs on 8chan.

ente: A particularly loud group are the so called identity-gamers. Their most distinctive feature is gatekeeping: They see themselves as “true gamers” while others, e.g. people playing mobile games, casual games, narrative games or people who are not white-cis-male are not and accordingly have no right to be part of gaming communities.

radow: Naturally most of those do not want to have anything to do with the terrorists, but share many of the same phrases, idols (Pewdiepie, Jordan Peterson) and ideology or make edgy jokes about the atrocities.

How did you perceive the coverage and the political discourse surrounding the attacks and their relation to the gaming scene? [Note: This question mainly focuses on the coverage of the Halle attack in German media.]

fuchsi*: My first reaction was “Not the ‘killer game’ debate yet again!”.

radow: Starting an in-depth conversation about racism, sexism, other forms of discrimination and toxicity in video games, gaming communities and gaming culture would absolutely be necessary.

fuchsi*: The public discourse, however, is very superficial, focuses too much on general game mechanics and tends to miss the actual problems.

radow: To be clear: Problematic content as well as mechanics do their part in attracting bigots and making them feel justified, but the discourse usually does not even reach this level of analyses. It usually does not cut much deeper than “Oh a Shooter – those are bad”.

ente: The defensive reaction of large part of the scene to these discourses itself isn’t particularly helpful to starting a critical debate, in which gaming communities would ideally begin to take responsibility for their problematic and enabling culture and policies.

When Nazis started coming to Hardcore concerts the scene reacted by developing the “Good night white pride” label and tried to exclude Nazis from their spaces and events. Does something similar exist in gaming? Why not?

ente: There is nothing of comparable reach and scope though many smaller communities have codes of conduct that sanction transgressive behavior.

fuchsi*: Parts of the scene do have a heightened level of awareness for these problems and accordingly there are pushes to confront and in some cases deplatform content creators, publishers and developers that perpetuate them. These often lead to severe shitstorms against critics and affected marginalized people who do speak up and it can be hard to cushion those attacks as communities since they often target individuals.

ente: One of the problems is certainly that many people do view gaming as fundamentally apolitical. That makes the circumstances quite a bit more difficult than it was in the hardcore context. Even positions that should be consensus everywhere, like “Nazis are not okay” are not universally accepted in some spaces.

radow: It’s generally much more difficult to exclude Nazis from online spaces and communities, because the spaces themselves are much more vaguely defined. When Nazis openly try to come to a concert, you can just throw them out – either as a community or in cooperation with the organizers. Online communities can sprawl over multiple platforms and in the few cases that the platform providers do react they just return the next day with a new account or on a new platform.

What could be done against toxic communities and Nazis in gaming?

ente: As gamers as well as as developers we can organize and strengthen our communities, e.g. by introducing codes of conduct. But big content creators, publishers and studios also need to take on their responsibility for their products and communities.

fuchsi*: Especially in regard to the aforementioned deplatforming of Nazis more needs to be done. Finding solutions for this that do not rely on the intervention of governments and huge tech companies has so far proven frustratingly difficult – and may in fact be impossible as long as Facebook, Twitter etc. (rather than their open source alternatives) remain as important as they are right now.

radow: And then – of course – there is classical antifa work: dedicated research and documentation of recruitment methods, praxis and structures of alt right, MRA’s etc. in gaming spaces.

Thank you for the interview!

Purple Sloth Studio

Purple Sloth Studio